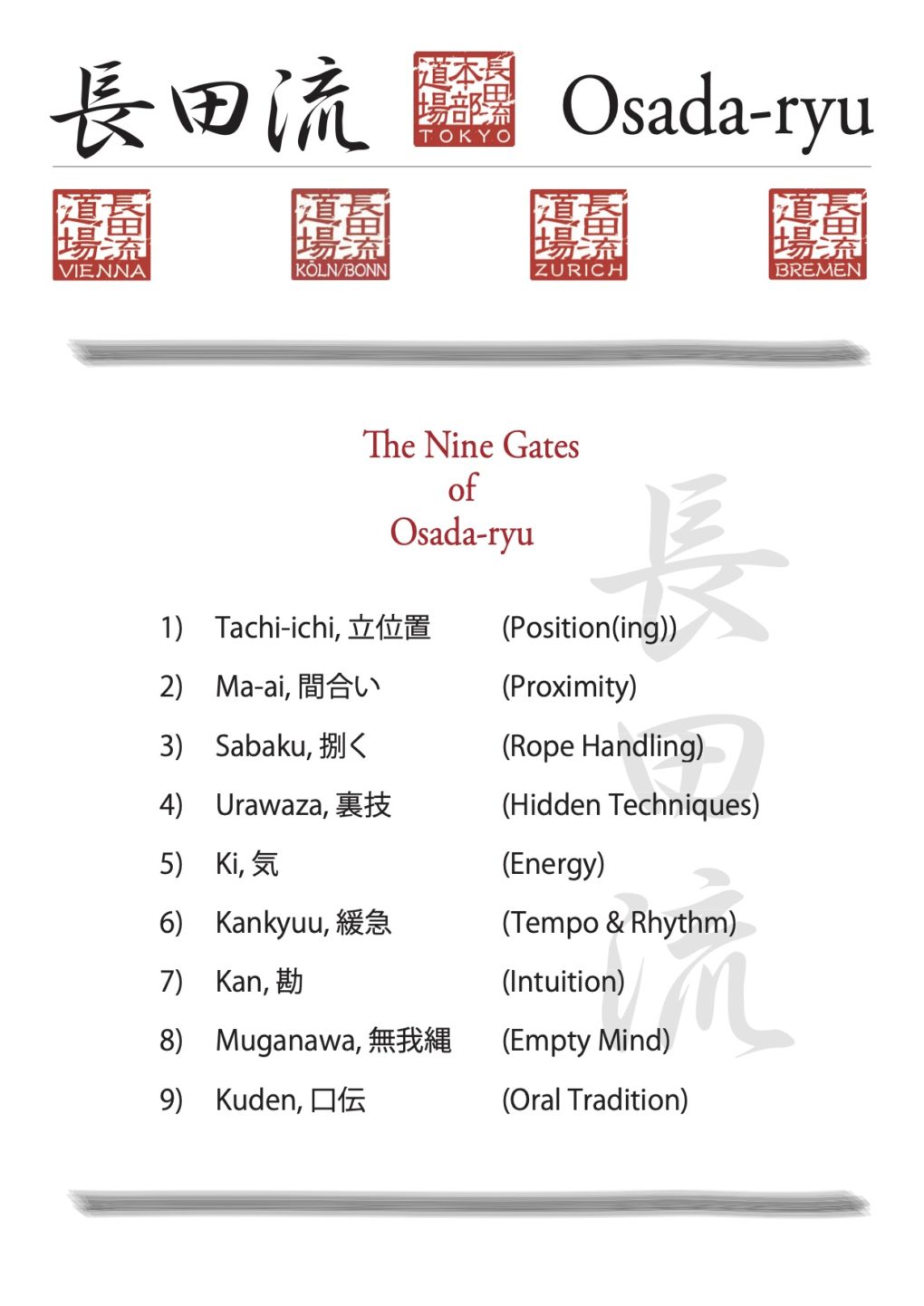

The 9 Gates are the theoretical and philosophical core of Osada-Ryû, because they describe the essential elements of teaching. All techniques are related to or express these concepts. The basic principles of the 9 Gates shape the teaching and approach in Osada-Ryû.

They permeate all kyû, every pattern and every technique.They also connect the individual schools in Tokyo, Vienna (run by Vinciens), Königswinter, Bremen, the S56 in Vogelsang and of course the Harukumo-Juku in Koblenz.

- Tachi-ichi, 立位置 – (Position(ing)) – Describes the position and attitude of Bakushi and Ukete.

- Ma-ai, 間合い – (Proximity) – Describes closeness and distance.

- Sabaku, 捌く – (Rope Handling) – Elegantly guide the rope with efficiency and little friction.

- Urawaza, 裏技 – (Hidden Techniques) – Interactions between Bakushi and Ukete, but not recognizable from the outside.

- Ki, 気 – (Energy) – Life force or energy flow describing the exchange between Bakushi and Ukete.

- Kankyû, 緩急 – (Tempo & Rhythm) – Dynamics and rhythm that fill the shibari encounter with tension.

- Kan, 勘 – (Intuition) – Intuitively anticipating the next steps, and emotional states during the shibari encounter.

- Muganawa, 無我縄 – (Empty Mind) – A special state of mind.

- Kuden, 口伝 – (Oral Tradition) – Oral transmission of knowledge by the sensei.

This content is difficult to teach theoretically because it depends on the interaction between the teacher and the learner. In each technique and pattern, these elements can interact differently and create new and interesting interactions.

Since each level of training focuses on different of the 9 gates, indiviudal emphases are set and adapted to the development of the learners.